Click for part 3

Saar Offensive, 1939

The 1930s truly was the calm before the storm. France and Britain, with the exertions of the ‘War to End All Wars’ behind them though still fresh in the memory, and their empires pretty much pacified, were enjoying a peaceful decade they did not want to end. The Allies watched the rising power of Adolf’s Nazi Germany with subsequent unease. As is well told, the Nazis became increasingly bold in their ambitions to dominate Europe; they seized Saarland, absorbed Austria before conquoring Bohemia, and with this global war commenced. France was not keen to attack Germany, given how the Battle of the Frontiers had gone for them in the last war (see part 3); plus the French feared the wrath of the Luftwaffe given its destructive capabilities observed during the Spanish Civil War. Yet, France felt they must try something to help the Poles now under attack, considering it possessed a strong army and Germany’s war machine had not regained its full strength after being hobbled by the Versailles Treaty; it could not yet fight on two fronts. With their backs momentarily turned to France, Germany was open to attack by the Armée de Terre.

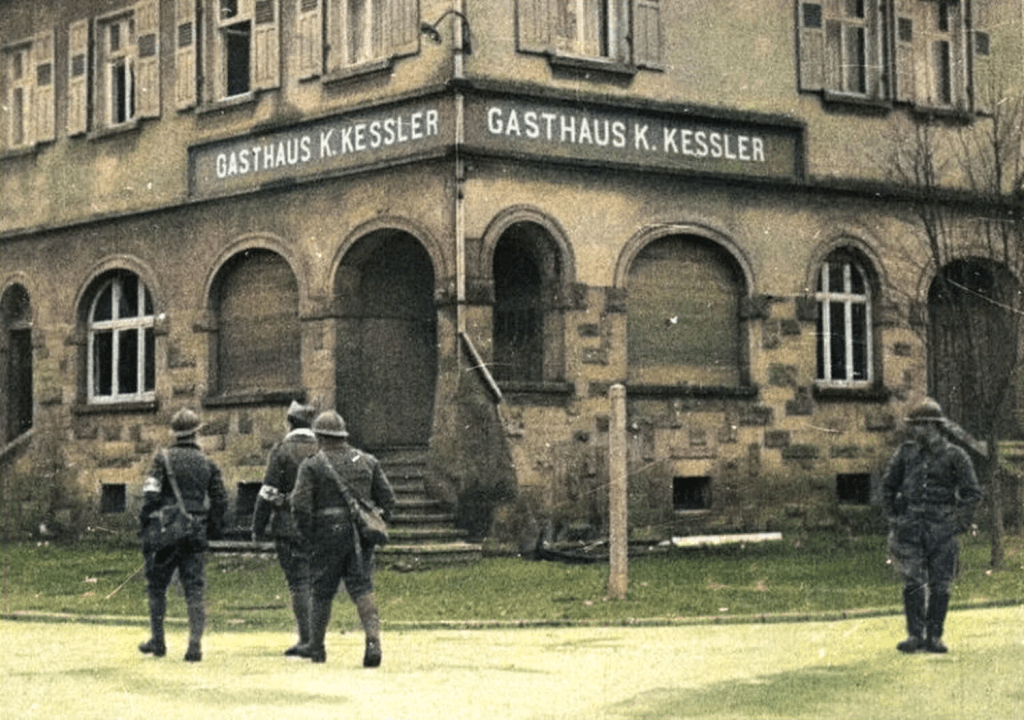

One week following the outbreak of war, General Maurice Gamelin launched 11 divisions into Germany along a 32-mile (51km) front near Saarbruecken and virtually strolled in. They advanced eight miles (13km) into enemy territory without a single shot being fired, capturing 12 towns. On the 12th, enemy troops counter-attacked the French in the Warndt Forest but were beaten back. By the 21st, however, the Poles were beaten and Gamelin realised the inevitable large-scale counter-offensive would be better defended behind their fortified border, so ordered his army to withdraw. As they did this, the French were engaged by a regiment of the Wehrmacht and there was some stiff fighting as the French backed out of enemy territory.

The French, though hardly defeated, failed to draw the Germans off from assailing the Polish in what was perhaps the most half-hearted and limp-wristed act of military aggression in European history, and they suffered a total 2000 casualties against the Germans’ losses of under 200. The French, with their formidable tank fleet and fortified lines, now braced themselves for what was to come…

Fall of France, 1940

The French faced the German juggernaught for the 3rd time in 69 years. In 1870, they acted with hubris and were floored. WWI went better with the aid of allies, though not before their initial lunge for a knockout punch missed to get a bloody nose in return. Now, this 3rd time, the French were going to let the enemy move first and it was they who would deliver a knockout blow. The plan was that any German invasion on their shared border could be halted by highly-vaunted Maginot Line whilst any attack north could be shouldered by the Benelux nations sufficiently long enough for France to counter-attack with perhaps the heaviest armoured force in the world.

On May 10th, the Phony War ended and it got very real when 3.3 million German troops invaded the Benelux nations. The French (plus British BEF), with more artillery but less tanks and aircraft, had the mindset that this was WWI part 2. The Germans, meanwhile, launched their evolutionary Blitzkrieg form of warfare. Fleets of Stuka dive-bombers were employed like highly mobile and precise artillery. Designed to ‘scream’ as they made their attacking dives, these bombers smashed any counter-attack or strongpoint that threatened the German’s progress and their psychological impact on allied troops was considerable. The Wermacht always looked to break through defence lines at their weakest points and they deliberately flooded the road network with fleeing civilians to gridlock French logistics and mobility. Also, the French armour was too scattered about to oppose the larger formations of German tanks. It was a harrowing ordeal as the French army tried to get to grips with an enemy that was forever charging forwards.

As General Gamelin’s forces were sucked into the fighting in the north east, the Germans managed to slip an armoured spearhead north of the Maginot Line through the Ardennes Forest – considered impassible by the French. This spearhead then raced to cut off the French in the north east, smashing through at the Battle of Sedan to reach the sea at Abbeville by May, 20th. The creme de la creme of the French Army – 1st, 7th and 9th armies – were now cut off. In the resulting Dunkirk evacuation, 140,000 were rescued, leaving 40,000 to surrender. By the 25th of June, Paris had fallen and most of France was in Nazi hands.

This was of course France’s worst ever military disaster. Over 300,000 dead or wounded; foreign occupation by the odious apparatus of the Nazi reich; the humiliation of southern France reduced to a vassel-state of the enemy’s. Yet, De Gaulle‘s Free French government-in-exile would continue the fight alongside Britain, and four years later France achieved her liberté.

Battle of Dien Bien Phu, 1954

After World War II, France was keen to re-secure control over her Indochinese holdings in order to regain a strategic asset as an incumbent world power. Yet the Indochinese, headed by the Viet Minh, had’d enough of foreign overlordship and so launched an insurgency in 1946 to which the topography was highly conducive. Viet Minh General Giap‘s pinprick, attritional warfare steadily bled the French military dry. By 1952, the French had lost control of North Vietnam outside of the Red River Valley. Later that year at the Battle of Na San, however, they successfully tried out a new ‘hedgehog’ defensive battle tactic whereby a large infantry force, supplied by air and defended by artillery, held a number of mutually supporting, interconnected outposts bristling with strongpoints to chew up the hard-hitting human wave assaults which Giap was having so much success with. By 1954, the French Government was about ready to throw the towel in, so General Navarre decided to recreate the Battle of Na San but on an even greater scale at Dien Bien Phu. Quite literally, the French were going to ‘go big or go home.’

Dien Bien Phu valley was occupied in November 1953 to which a base was built up, complete with its own airfield, to consist of 14,000 troops and 60 heavy artilley pieces. General Giap saw the strategic significance of this move and pushed his poker chips into the table centre. Unlike at Na San, the Viet Minh now possessed heavy artilley and anti-aircraft cannons meaning they could now bombard the French into submission, knock out their airfield and repel air supply sorties. Over the coming months, the Viets first created a supply artery to the valley then emplaced 105mm howitzers into camouflaged hillside bunkers where they could imperviously deluge the French with fire. Giap also deployed the bulk of the Viet Minh’s strategic reserve to the battlefield – about 50,000 troops. On the 13th of March, this most epic of post-WWII battles commenced. The French were dismayed that their two most northern bastions – Beatrice and Gabrielle – fell under a maelstrom of cannon fire and waves of infantry in the first 48 hours in which two battalions were destroyed plus another (Thai battalion) defected. Morale plummeted; artillery commander Colonel Piroth pulled a grenade on himself over his failure to knock out the enemy’s artilley and it is claimed base commander de Castries retreated from his duties to his bunker. There was then a lull as the Viets moved in to assault the closer bulwarks around the airfield named Anne Marie and Dominique. There, elite French paras and legionnaires matched up their superior combat prowess against the Viets’ rigid human wave assaults. By the 7th of May, however, the defenders were burned out and in a final all-out assault, the Viets overran the airfield and headquarters. With the French surrendered, almost 12,000 were taken into captivity of which over 8,000 were never seen again.

This defeat in the ‘Last Valley’ was the nail in the coffin for the French Indochinese Empire and they signed a peace agreement one month later. It was a traumatic disaster for the French, certainly at the political level; their armed forces had been bested by an army of Asian peasant insurrectionists. It would now be ‘out of the fire and into the frying pan’ with the upcoming insurgency in North Africa.

Battle of Djebel Bouk’hil, 1961

The three decades following World War II were marked by the breakup of Europe’s merchantile empires. The French, British and others had fought for their ‘freedom’ in the war, so it was understandable that their colonies’ peoples, many of whom had served in the war effort, wanted freedom of their own. Algeria was no exception, however because the French had been taught that ‘the Mediterranean separates Algeria from the Métropole as the Seine separates Paris’, the eight-year long Algerian War was a bitter one that rent the political Right from the rest of the French political establishment, resulting in not one but TWO army putsches and the dissolution of the 4th Republic by the war’s end. Headed by the National Liberation Front (FLN), the war for independence commenced on November the 1st, 1954 and France’s violent crackdown on pro-independence activists galvanised support for the FLN amongst Algeria’s population. The war turned very messy indeed with numerous war crimes committed by both sides, yet the French people were evidently suffering from war fatigue. In January 1961, a referendum voted 75% in favour of Algerian self-determination and so President De Gaulle opened peace negotiations with the FLN. In June, de Gaulle announced on TV that fighting was “virtually finished”. It is curious therefore that in September, five months before the war’s end, the French army launched a large operation to capture leaders of the FLN upon Djebel Boukhil.

On 16 September 1961, the French learned about a meeting of FLN commanders, including Colonel Chabani, guarded by 370 mujahideen fighters on the Bouk’hil mountain. The next day 12,000 soldiers were trucked in to put a cordon around the mountain and cut off all escape routes. The French then tried to subdue the Algerians with fighter-bombers and artillery strikes. The Algerians were only lightly armed against this enemy surrounding them, but they held the high ground – a suitable metaphor for the contrast in morale between the two sides. When legionnaires attempted to assault the Algerians up the rugged mountain slopes, the Mujahideen fought back like barbary lions and repelled the French who suffered 400 casualties. The next day, the French bussed in 2000 reinforcements but the Algerians held them off before disguising themselves as goat herders and, somehow, slipped out of the cordon along a northerly route.

Chabani and his men escaped, suffering just nine dead in the two-day battle compared to French casualties of 700 men and three aircraft shot down. In March of 1962, a ceasefire came into effect and the war ended, and in July of that year, the People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria gained its independence. The French Empire had now evaporated.