Click for Part 1

Battle of Maeva, 1846

Although little is documented of the fighting itself, the French lost a shore party of marines in what has been described as a massacre by some, on the island of Huahine, modern-day French Polynesia. The Leeward Islands were divided between four kingdoms: Tahiti, Huahine, Raiatea and Bora Bora. The conflict was ostensibly about the French desire to spread Catholicism to the kingdoms that had already adopted Protestantism and were backed by the British. The Franco-Tahitian War broke out in 1844 after Queen Pōmare IV expelled French missionaries and incured the ire of the French. After invading and subjugating Tahiti by 1846, France then tried to impose the suzereinty of Tahiti over the rest of the Leeward Islands. Yet on Huahine, they came up against the formidable force of warrior-queen Teriitaria.

Rear-Admiral du Petit-Thouars landed 400 troops on the island and planted the French flag as an open challenge before destroying the town of Fare. Teriitaria responded by assembling her warriors on a nearby island and sailed to Huahine. The French then advanced on Maeva but the locals and Teriitaria’s troops, desperate to save Maeva from destruction, made a stand. A detachment of marines from the ships Uranie and Phaeton, led by Ensign Clappier, were wiped out in a two day battle against their more poorly armed opponents. 24 French were slaughtered and 45 injured to the Polynesians’ loss of three defenders in the fighting in which Queen Teriitaria is described “…musket in hand, and with half a dozen cartouch [sic] boxes belted round her slender waist, was there to encourage her people.”

With the menace of British warships loitering in the vicinity, the French abandoned their operation on Huahine and ended their blockade of Raiatea, thus, liberating the Leeward Islands. Tahiti remained under French control however and the Leewards would be subjugated by the French by the end of the century.

Siege of Petropavlovsk, 1854

An Anglo-French force failed to knock out Petropavlovsk as a base of Russian naval operations in the Pacific during the Crimean War. A desire to check the rising power of Russia and fears of the instability that would occur if the ‘sick man of Europe’ – the Ottoman Empire – was knocked out by the Russian Empire, caused war to break out. France’s Napoleon III – allied this time with the British as well as the Turks – wanted to use the war to show the world that he possessed his uncle’s talents. Whilst most of the war’s action raged in the smallest of the ‘severn seas’ – the Black Sea, the largest of the seas – the Pacific Ocean – also saw the belligerents come to blows. Britain and France were concerned that the Russians might deploy their one major warship, the 44-gun frigate Aurora, to menace trade routes to California. The allies assembled a six-ship task force carrying 1700 troops to neutralise the Russian threat. Russian Admiral Putyatin decided that the most prudent course of action would be to withdraw his remaining forces to Petropavlovsk port on the Kamchatka penninsula. There, the Allied task force moved in.

In the 1st phase of the siege, British task force commander Admiral Price decided to neutralise a fortified spit of land behind which the Aurora sheltered with a naval bombardment and landings of marines, and the attack was successful in its aims; the Aurora was heavily damaged, although the French ship Forte had to withdraw from action. During the next phase, a series of naval bombardments and amphibious landings took out more outlying shore batteries, although the landing parties were driven off each time by the vigourous counter-attacking by 900-odd Russian soldiers, sailors and sharp-shooting hunters. During these couple of days, the allies lost their proverbial rudder; Admiral Price suffered an apparently suicidal, fatal gunshot wound while the French senior offier, Counter-Admiral Fevrier-Despointes, fell gravely ill. With French morale now slipping below the waterline, they only reluctantly agreed to the next phase; a land assault of four groups, the bulk of which were to invade the town from the north after securing Nikalski Hill. The French group in charge of hauling artillery atop the peak could not find the rumoured track leading up, so dithered. Meanwhile, hundreds of other troops and sailors tried to advance upwards but thick brambles made the going slow. Russians sharpshooters took a terrible toll on their officers to the extent the attack broke down. The allies were then driven back to their beachhead at the point of a bayonet charge and further decimated as they scrambled to evacuate to their ships.

The French and British had failed, so abandoned their siege of Petropavlosk with over a hundred French dead and wounded (so too for the British). The following year, another Anglo-French fleet returned and took the now abandoned city in May of ’55.

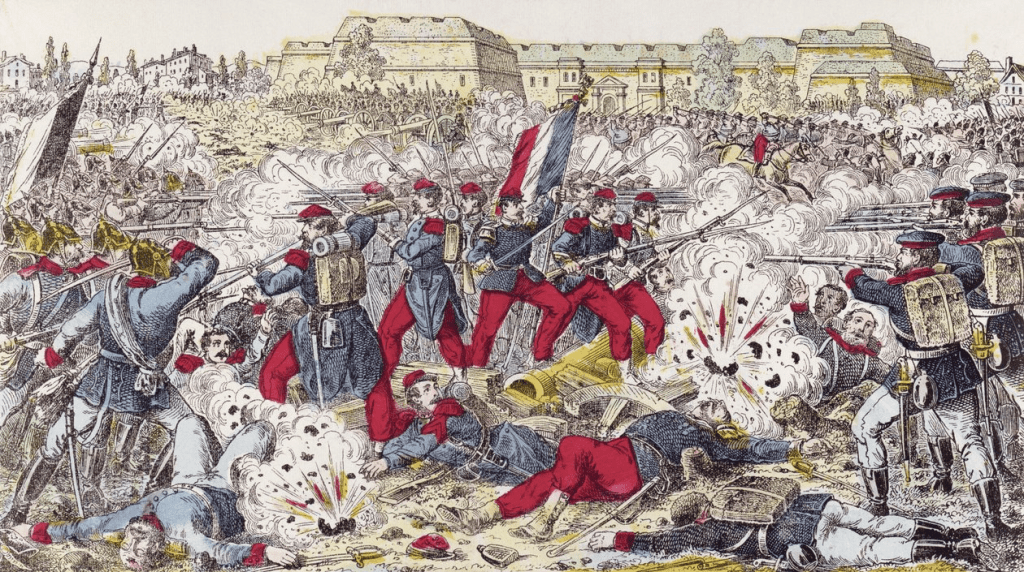

Battle of Puebla, 1862

In Mexico, an overly cocksure assault on an enemy position left the French Army’s prestige in tatters and put the Republican’s war effort on a firm footing. France’s initial reason for the military expedition into the northern Latin-American nation was to recover debts. Yet Napoleon III was still trying to fill the big boots of his diminutive uncle and so the campaign developed into one aimed at establishing a puppet-monarchy that would reinstate French influence in the Americas. After capturing Veracruz in December 1861 (initially alongside Spanish and British forces whose governments also sought debt repayments), General de Lorencez marched a 5700-strong army east to remove the Republican government from their seat of power in Mexico City. Yet Puebla de los Ángeles, guarded by the conjoined fortresses Loreto-Guadalupe, stood in the way and a ragged Mexican army of almost 3800 gathered there hoping to stop the gilded French force. The Gauls possessed one of the finest armed forces in the world with long-range rifles which far outgunned the Mexicans’ antiquated muskets. As such, the French army’s march east across the Mexican landscape was imbued with elan. As they drew up around Republican positions, they stamped their mark with loud bugle cries and complex bayonet drills while Loreto and Guadalupe’s defenders braced themselves behind their thick walls.

With the two Mexican forts atop a steep hillock and the Mexican army sheltering below on their right flank, Lorencez had the reckless idea to storm Guadalupe with two light infantry battalions in order to bring artillery up to the fort to shell the Mexicans below. In truth, both forts needed to be stormed because they were able to provide mutually defensive fire if one or the other were assaulted, but the French lacked the numbers to attempt that. They were tired after the long march, unacclimatised to the desert heat and clearly underestimated the enemy. Whilst a barrage of French cannon balls bounced off the hillside, the zouave infantry advanced up the rugged hillside but were raked by fire from both forts (plus adjoining wall) and thus repulsed. The zouaves reformed and advanced on Guadalupe once more while de Lorencez’s marine infantry attacked the main Mexican force. Yet the Latinos, with their backs figuratively against the wall and literally behind it, and taking heart that they might actually win this fight, repulsed the Gauls again with a desperate bayonet charge. De Lorencez now commited his reserves to an all-out assault before being informed his artillery was out of ammo. He attacked anyhow but the exhausted French could not drive their foe from the battlefield. With a Mexican counter-attack, the French were defeated.

Morale in the Republican cause soared and the city name of Puebla de los Ángeles was changed to Puebla de Zaragoza in honour of the Mexican army’s victorious general. De Lorencez was dismissed before the French could take Mexico City 12 months later. Ultimately the Republicans would oust the European superpower in 1867.

Battle of Sedan, 1870

Certainly one of France’s worst ever military disasters that led to the fall of the Second French Republic. French political opinion at the start of 1870 viewed France as the dominant alpha of the continent, established by its many military accomplishments the most recent being its victory in the Franco-Austrian War of 1859. The proto-German nation – the North German Confederation, headed by Prussia – was perceived as a youthful, boisterous upstart who was still young enough to be put in its place. In truth, that French alpha was proud, hubristic and felt threatened by the lean, testosterone-fuelled youth growing into a strapping giant.

France, alarmed by Prussia’s aggression in the Austro-Prussian war of 1866, precipitated conflict in July of 1870 with an invasion of the German confereration with its Army of the Rhine. This army was battered into submission and besieged in Metz by the German 1st and 2nd Armies. Napoleon himself accompanied France’s 2nd-line army – the Army of Chalons commanded by Marshal MacMahon – to rescue the Rhine army. Yet, the German 3rd and 4th Armies – commanded by Field Marshal von Moltke – ran rings around them. By 31st of August, they were harried into Sedan with its antique fortress where the French might be allowed a moment’s respite. Napoleon’s massive 130,000-strong army was outnumbered by von Molke’s 200,000 men and, on September 1st, they surrounded the French to cut off their escape. Whilst the French had the best rifles, the Germans had far superior artillery. Their tactic was to quickly manoeuvre it around the battlefield to pound their enemy into submission. The French tried to break out with cavalry attacks but failed. With 400 German guns mounted in a semicircle on the high ground around the town, Napololeon’s army was done for. He surrendered by mid-afternoon.

French casualties were about 18,000 dead and injured and France’s Army of the Rhine and Army of Chalons were now neutralised – the Army of the Rhine barricaded in Metz until its surrender in October. Emperor Napoleon III was also now a prisoner of war – an utter humiliation for the republic. Von Moltke went on to besiege Paris after the 2nd Republic was overthrown to be replaced by the Government of National Defense. The French continued the fight with the large manpower levee at their disposal but submitted to the Germans in January 1871, losing the industrial heartland of Alsace-Lorraine and five billion Francs as the price of defeat.

Battle of Bang Bo, 1885

France had been making increasingly aggressive forays into northern Vietnam in the latter 19th Century. This provoked the Qing Dynasty to deploy its forces and trigger the Sino-French War in 1884. By February 1885, the French seemed to have the beating of the Chinese after they took Lang Son then relieved the siege on Tuyên Quang. In March, General de Négrier took his 2nd Brigade from Lang Son up to the Chinese border. There, he expelled the battered remnants of the enemy army from Tonkinese (Viet) soil before both sides awaited reinforcements.

After 2nd Brigade fought off a Chinese raid, de Negrier decided to attack enemy forces amassing around Bang Bo with 1600 men. The General ordered their main trench-line to be attacked from the front and rear, sending Lieutenant-Col. Herbinger with two battalions around to the rear of the trench line. Yet, Herbinger got lost in thick mist. De Négrier, unaware of this, mistook Chinese troops moving up to the trench for Herbinger’s two battalions and ordered the 111th Battalion to deliver a frontal attack. They charged, but were shredded by a maelstrom of enemy fire from both their front and sides. After fighting hand to hand, the 111th fell back in disarray, abandoning their wounded to be beheaded. The rest of the Chinese army, numbering in the tens of thousands, now advanced on their assailants and the French were forced to retreat under intense contact. Finally, the French reached Lang Son but were battered, exhausted and utterly dismayed at the humiliation they’d suffered in which they suffered almost 300 casualties.

Four days later, however, the Chinese tried to follow up their victory with an assault on Lang Son, but with artillery in support, the French emphatically repulsed the Chinese. So, the French proved they were still far from beaten. Yet, De Negrier was seriously wounded in the battle so command passed to Herbinger, and this is when things turned calamitously for the French. Herbinger, ill with malaria and in sharp contrast with his fellow officers, was evidently intimidated by the Chinese army that had so brutalised 2nd Brigade at Bang Bo. He was convinced 2nd Brigade was in serious danger of being annihilated by the enemy if they didn’t clear out. So, he withdrew south, with artillery pieces and even the treasure chest abandoned in Herbiner’s haste to move.

Other French units also abandoned their northern positions to conform with Herbinger’s timid retreat, and in the face of an enemy with little will to take advantage; the Chinese had been licking their wounds and were shocked to hear of Lang Son’s evacuation. The political fallout back in Paris was severe, causing the fall of Prime Minister Jules Ferry’s government. The French ended a war that had otherwise been going quite well for the them. France’s appétit for colonial expansion was lost.