Click for part 2

Apia Cyclone, 1889

It was during the peak years of Western-state nationalism when countries like the USA, Britain, Germany and Italy strutted around the world with their chests puffed out that a small US Naval squadron was wrecked in rueful circumstances.

A storm had been brewing in the Samoan Islands since 1886 with the commencement of the 1st Samoan Civil War. The USA had guaranteed protection to the island nation in return for acquiring a refuelling station while the German Empire had territorial ambitions in Samoa and gave support to a rival of the incumbent head of state. This culminated in a military face off between the two nations in Samoa’s Apia harbour. Three German and three US Navy warships were present in the bay during cyclone season. Seamen and locals alike could tell an actual storm was building and all the ship’s captains knew that they should ride out any storm in open water, not boxed in where the 100 mph (160 kmh) winds would batter them to pieces in the harbour. Yet neither side would budge due to their pride and bravado, and so both navies took no precautions in the face of the oncoming storm. The ships began to evacuate only at the very last minute and were all crowded around the entrance to the bay when the cyclone hit. Chaos reigned; the steamer USS Trenton was tossed against the beach, dragged back into the sea and wrecked on a reef. The sloop-of-war USS Vandalia was smashed into the same reef and her surviving crew spent a miserable day and night clinging to her rigging before they were rescued, by which time 43 of them had drowned. The gunboat USS Nipsic was thrown high on the beach with eight of her crew missing or dead and internal systems totally wrecked. She would however later be refloated and reconstructed in Hawaii. The German ships fared even worse.

It was a disaster one historian described as “an error of judgement that will forever remain a paradox in human psychology.” Neither side wanted their position weakened by leaving the harbour, so both of their positions were wrecked by staying put. 52 US Navy sailors perished in total. Samoa would later be divided between America and Germany.

Battle of Cardenas, 1898

The 16-week long Spanish-American War was described by one US Ambassador as “a splendid little war.” It established the USA as the ‘big fish’ in the Caribbean going into the 20th Century. Yet, a US Navy squadron got a nasty little surprise when it attacked the Cuban port of Cardenas. It was to be no battle between behemoth battleships but on May, 11th Captain Todd’s small squadron of craft, suitable for inshore operations and bristling with torpedoes and light cannons, sailed into the Bay of Cardenas looking for a fight. Moored within, a worthy opponent – three gunboats, one of which had already driven off one of Todd’s boats from the bay days before.

USS Winslow probed the shore to look for the enemy and spotted a steamer. Over a mile out, the Spanish ship suddenly opened fire on the Americans and a frantic firefight erupted. For over an hour they duelled. One of the enemy’s first shots on target smashed into Winslow‘s boiler room and steering. She floundered before another shot knocked out her engine room. Winslow and the other ships fought back hard, shelling the town and incapacitating the Spanish steamer. But Winslow was almost dead in the water and needed rescuing. USS Hudson started towing the stricken torpedo boat away but then another shell struck Winslow to starboard, taking out 35% of her crew. USS Winslow was rescued and would be towed for repairs but the US Navy avoided Cardenas for the remaining war after this bruising punch-up.

Battle of Balangiga, 1901

Despite the conditions the USA was founded in, America was not sympathetic to the Filipinos’ own ‘War of Independence’ that had commenced in 1896 because it clashed with the USA’s ambition for an overseas empire of her own. The First Philippine Republic had risen up initially against Spain, but when she was defeated in the Spanish-American War two years later, it was the Americans who needed to be kicked out for the Filipinos to attain independence.

In September the ‘Patriot’ army operating on Samar Island planned to neutralise a US force in Balangiga with the aid of the city’s citizens. Soldiers of C Company, 9th Infantry Reg. had settled in well with the town’s folk whilst they worked to cut off supplies to the revolutionaries. Relations became strained so a plan was set in motion between the police chief and local army commander; they would host a fiesta and get the Americans drunk then attack them as they slept it off. The fiesta provided a cover to bring in hundreds of attackers, ostensibly to set up the fiesta, but in reality to overwhelm the US infantry before they could bring their firepower to bear. On the morning of the 28th, the sun had yet to crest above the palm trees and rooftops as the Americans dozed or ate breakfast whilst others overlooked a work detail of prisoners in the plaza. Then all hell broke loose; the prison labourers knocked out a private sentry then rushed C Company’s mess hall armed with Bolo machetes. At this, church bells rang out and conch shells were blown to herald an onslaught by 500 attackers. Around the barracks and mess tents, the soldiers fought desperately with whatever they could grab hold of; kitchen utensils, chairs, knives before they could be hacked to death. Some soldiers got hold of rifles and started killing their assailants. With this, the attack petered out and the rebels called off their attack. Yet C Company was almost wiped out with just four men left unscathed. Shaken, the survivors fled by boat.

The hyperbolic US reaction stateside compared the Balangiga ‘massacre’ to Little Bighorn (see part 1). In response the US slaughtered thousands in their punitive ‘March across Samar’ in December of that year.

Battle of Carrizal, 1916

Away from the killing-fields of Northern Europe, trouble rumbled south of the border down Mexico way. A revolutionary general named Pancho Villa rose to such prominence that he was one of the no.1 figures in Mexico’s coalition government of 1914 and viewed favourably by the US Government, They then switched their favour to Villa’s rival, Carranza, whom they aided logistically to defeat Villa’s forces in battle. Out of spite at this percieved betrayal, Villa raided the US town of Columbus so the US army launched a large expeditionary force to cross the border and neutralise Villa’s forces in turn.

Three months and 60 miles (100km) deep into the military operation, two troops (90 men) of the 10th Cavalry Regiment were scouting out Carrizal where it was understood Villa was holed up injured, yet 300 Mexican Army soldiers blocked their path with orders to open fire on any US troops not heading north. The Mexicans issued a warning to the cavalrymen’s commander, Capt. Boyd, but he decided to attack the Mexicans anyhow. In the resulting skirmish, 40 cavalrymen were killed and wounded, including Captain Boyd, plus 24 were captured, although the Mexicans suffered even more casualties.

This clash of arms almost brought the two nations to war again, and President Wilson decided to step back from the brink given the USA’s upcoming fight in Europe. The expedition was thus recalled home. Pancho Villa was assassinated in 1923.

Honda Point Disaster, 1923

The US Navy lost no less than seven warships off the coast of California in a major navigational calamity. 14 Clemson-class destroyers of Destroyer Squadron 11 (DesRon 11) were sailing from San Francisco to San Diego on a training voyage. The squadron was commanded by Capt. Edward Watson and was sailing at speed to replicate wartime operating. It was the 8th of September. Earlier that day, DesRon 11 had recieved a distress signal from the steamship SS Cuba. She’d ran aground on this dangerous stretch of coastline but Capt. Watson ordered his squadron to continue on. Cuba’s fate was ominous and had the destroyers diverted to help the stricken ship, it might’ve saved them from the disaster they were sailing into.

DesRon 11 was sailing south in a closely packed single column with the plan to turn east once past Point Arguello to sail through the Santa Barbara Channel. Yet Watson and his navigators had made a serious error. For one, they chose to dismiss their newfangled radio navigation technology that was telling them they were not as far south and as far offshore as they estimated themselves to be. Secondly, extraordinary ocean currents, stirred up by the Great Kanto Earthquake a week prior, had the effect of misleading the navalmen about the rate of knots they were moving at and how far south they’d subsequently sailed. So, when Capt Watson ordered his ship line to turn east in heavy fog, the 14 ships headed smack bang into the coastline, and not just any coastline, a particularly treacherous spot dubbed the ‘Devil’s Jaw’ due to the jagged, bared rocks poking out of the sea. At 21:00, the lead ship USS Delphy slammed into the rocks at 20 knots and was brought to a violent, shuddering halt. She quickly sounded her alarm for the ships close behind but it but it did not help them. USS S. P. Lee also ran aground; USS Young rode over submerged, jagged rocks that tore into her hull, flooding and capsizing her – 20 of her crew perished; USS Woodbury swang her wheel starboard but struck an offshore rock. Three more destroyers followed on like a motorway pile-up. The last seven ships manoeuvred in time to escape disaster.

Seven ships were lost and 23 men died in what was the US Navy’s worst ever peacetime loss of ships. And 11 officers were court-martialed – the largest single group of officers ever court-martialed in the U.S. Navy’s history.

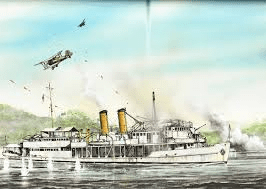

USS Panay Incident, 1937

Though hardly a ‘disaster’, the loss of a US Navy patrol ship in the calm period before the proverbial storm was a jarring one. The US Navy maintained a presence of patrol vessels on China’s Yangtze River from 1854-1949 called the Yangtze Patrol and the USS Panay joined the patrol in 1928. This river gunboat was armed with three 3-inch (76mm) cannons, it weighed over 470 tonnes and had 59 crew. Because China was a fairly lawless country, the Panay gave protection to US shipping and US nationals in cities like Nanjing. Then when Japan invaded China in 1937 and approached Nanjing, the Panay helped evacuate US citizens from the capital before retreating upriver with other shipping once the Japanese occupied the city.

On the 12th of December, with the ostensible aim of attacking Chinese forces that had fled there, Japanese aircraft were ordered to attack ‘all and any’ shipping upstream, despite being aware that this included USS Panay (plus other Western naval craft). The Panay, with the Stars and Stripes clearly emblaizoned on her side, subsequently came under attack. She was hit by two bombs and strafed by nine fighters. As she slipped under the murky water, small boats rescuing her wounded were machine-gunned by the Panay‘s circling tormentors. She sank with three dead. Royal Navy boats eventually rescued the survivors, including 43 wounded.

In the aftermath, Japan was contrite about the attack and claimed it was a mistake. They paid the US Govt. $2,000,000 a year later and the matter was settled, supposedly…