Part 3

Battle of Spion Kop, 1900

The British, reinforced after the trauma of ‘Black Week’, were still labouring to relieve Ladysmith after almost three months of siege. General Buller decided on seizing Spion Kop because the hill stood slap-bang in the centre of Boer positions around Ladysmith. 20,000 troops, Mahatma Gandhi and Winston Churchill included, and General Woodgate in direct command, moved to seize the summit on January the 23rd.

Making the ascent in dense mist and pitch black are never the best conditions to navigate in, so when 1,700 infantry captured the lightly held hill-crest, dawn revealed the truth; they held a lower plateau, overlooked by three crests of the true summit – and they were occupied by the enemy. Woodgate had come prepared to entrench but hill-rock restricted such efforts. British positions came under pitiless shelling and sniping. The Boer command knew their hold over the summit was still vulnerable so ordered 300 commandos into a rare frontal assault. The fighting raged, vicious, close-quarter; the British, lunging with fixed bayonets, Boers, slashing with knives, their rifles cracking bones. They reached the crestline before they could be checked. A stalemate now developed around the Kop and casualties continued to mount. General Woodgate and a couple of his staff officers then fell leaving the British soldiers pinned down, confused, and now leaderless. Hard fighting continued and their positions were held with the aid of reinforcements. Although some of the men were cracking under the strain, more fresh troops seized the summit. Victory for the Brits seemed to be within their grasp because the following morning, the shattered Boers actually withdrew from Spion. The surviving British commander was ignorant of this, however, and believed Spion could not be held, so he, too, withdrew for the Boers to quickly return.

The British suffered 1,500 casualties in yet another defeat. The tables soon turned for the Brits as their massive war machine went through the gears to ground the Boer Republics into submission. Alas, the Boers ‘won the battles, but lost the war.’ The British Empire’s veneer of impenetrability was now gone, however.

First Day of the Battle of the Somme, 1916

World War I lives in our memory for the callous, almost industrial-like efficiency countless soldiers’ lives were snuffed out on the meat-grinder battlefields of northern France. And of all the times the British hammered in vain at the German shield, at the Somme many thousands of men were lost in an instant. This battle followed the format of most on the Western Front but on an obscenely large scale. For over four months 2.5 million Allied soldiers, over half of whom were drawn from the British Commonwealth, attempted to give the Germans a bloody nose in 12 sub-offensives, each a major battle in its own right.

Massed assaults of infantry were preceded by epic artillery bombardments that rarely had the debilitating effect on German trenches British Army HQ planned for. Once over the top, the infantry had to face scything machine gun fire before they could reach German trenches. The nadir was reached on the first day of the battle. Masses of Fourth Army ‘Tommies’, shredded by bullets and blown to pieces by artillery shells across a hellscape of destruction and din, suffered 57,000 casualties including 19,000 dead. It is the highest death toll ever suffered by the British Army in one day.

Kilmichael Ambush, 1920

The Irish War of Independence was a low-level guerrilla war with little conventional fighting as the Irish Republican Army (IRA) lacked the arms and ammo. IRA ‘flying columns’ were adept at ambushing isolated security forces, however. The British deployed a paramilitary force to support the police and these consisted of WW1 army veterans who quickly became notorious for their violence and ill-discipline towards the Irish populace. Subsequently, these ‘black and tan’ units were prioritised for ambushes and the most deadly of these occurred in County Cork in late November.

Three dozen IRA soldiers carefully prepared an ambush for 18 ‘black-and-tans’ travelling in two lorries. It was triggered when the IRA commander managed to flag down the first lorry then hurled a bomb at the cabin, signalling the surrounding IRA to open fire. A savage, close-quarter fight erupted. The black and tans were sitting ducks and were gunned down to a man, just one survivor was left for dead. For the British Government, although the numbers lost were negligible it alarmed them how easily these elite troops were wiped out. For the Irish, it was a morale boosting victory that ensured their fight for independence would grow and ultimately succeed.

Sinking of HMS Royal Oak, 1939

Whilst plenty of large warships have sunk in the Royal Navy’s history, taking down hundreds of sailors each time, the sinking of HMS Royal Oak stands out because it jarred the British out of a period of calm and into the carnage of World War II. HMS Royal Oak was a 30,000-ton Revenge-class battleship armed with 15-inch (381 mm) guns and 1,200 crew. By 1939, as the war was still in its ‘Phony’ stage, the battleship was showing her age. She was relegated to defending the Scapa Flow naval bastion with her decent anti-aircraft armament.

The German Kriegsmarine, however, was scheming to send a submarine to attack Scapa Flow. An Aladdin’s cave of targets was just waiting to be torpedoed there. In what Sir Winston Churchill described as “a remarkable exploit of professional skill and daring”, submarine U-47 managed to sliver past blockships and islands obstructing entry into Scapa anchorage to sink the Royal Oak with four torpedoes. She sank in 13 minutes taking down 834 souls, including Rear-Admiral Henry Blagrove. 134 boy-seamen, the youngest just 15, also had their blossoming lives extinguished – the most in any one ship loss.

The result of this surprise raid on Britain’s premier naval base meant it had to be virtually abandoned whilst Admiralty upgraded its defences. It struck an ominous tone for what was to come.

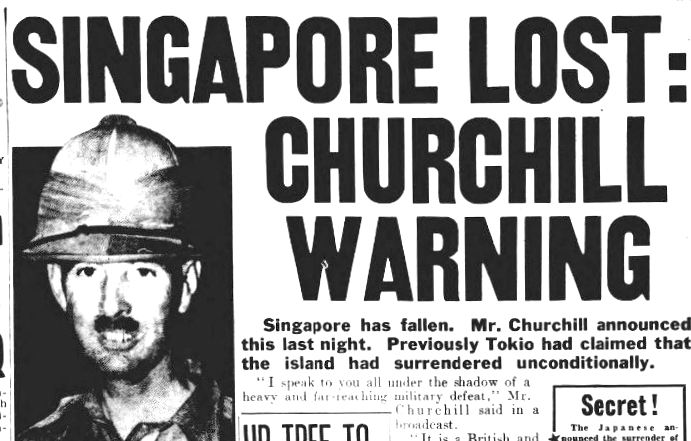

Fall of Singapore, 1942

At a time when Britain was suffering disasters left, right and centre, the Fall of Singapore was the worst military disaster to ever befall the British, traumatising Prime Minister Winston Churchill for years after, such were its consequences to British global standing.

Singapore was supposed to be a bastion of sea power that could host a formidable fleet and be guarded by massive naval artillery pieces manned by a large garrison. Yet Britain’s illusion of strength in the Far East began to unravel just a day after Japan’s entry into WW2. Japan invaded Malaya, and because the British had overestimated how impassable the Malayan jungle was and were anyhow under-resourced, the Japs managed to capture the entire peninsula in just seven weeks. Now, all that stood between the Japanese and ‘Fortress Singapore’ was a strait 10 miles (16 km) wide.

The aforementioned garrison numbered 85,000 Commonwealth troops (including a full division of British) plus hundreds of heavy guns. Failures of command-and-control meant that a soft spot in the north-western coast defences was identified and exploited for the Japanese force, outnumbered 2-to-1 by Commonwealth troops, to secure a beach-head. Despite some resolute defending, particularly by Australian battalions, central command failed to gain the tactical initiative and defending forces were pushed inland into urban areas. A week beyond the initial landings and British supplies were running low; the island’s water supply was being bombed and was failing, spelling doom for any hopes they could hold out. 5,000 fell in the defence of Singapore and the remaining 80,000 were taken prisoner. A total 130,000 Commonwealth troops in Malaya and Singapore, including 40,000 British, trudged into captivity after just nine catastrophic weeks of defence.

Battle of Imjin River, 1951

Four years after what is regarded as the moment the British Empire ended – the partition of British India – a battalion of British infantry was effectively destroyed during the Korean War. By 1951, the military initiative had been seesawing between the two adversaries as the American led UN struggled to blunt the human wave assaults of the Chinese ‘Red Wave’. In late April, the Communists went on the offensive again and attacked the British 29th Brigade, thinly stretched out over 12 miles (19 km).

Over the next few days, the brigade was forced back from a defence line on the Imjin. Despite tenaciously defending their positions, the Chinese were simply too many and swamped any allied unit that couldn’t conduct a fighting withdrawal quickly enough. One of the brigade’s four constituent battalions, 1st Battalion the Gloucestershire Regiment, was one of those units. Its soldiers paid the price for their stubborn defence of the Imjin River by getting cut off. They withdrew to Hill 235 to make a final stand and hope forlornly for rescue. A number of allied counter attacks were made to try to effect this, yet failed after two days of fighting. The Glosters were exhausted and many were wounded. Their commander, Colonel Carne, surrendered. Himself and 459 soldiers were marched into Chinese captivity.

The battalion was effectively destroyed whilst 29th Brigade was forced to beat a hasty retreat. 1st Battalion’s sacrifice is generally regarded to have prevented the Communists from capturing Seoul later.

Dishonourable Mentions

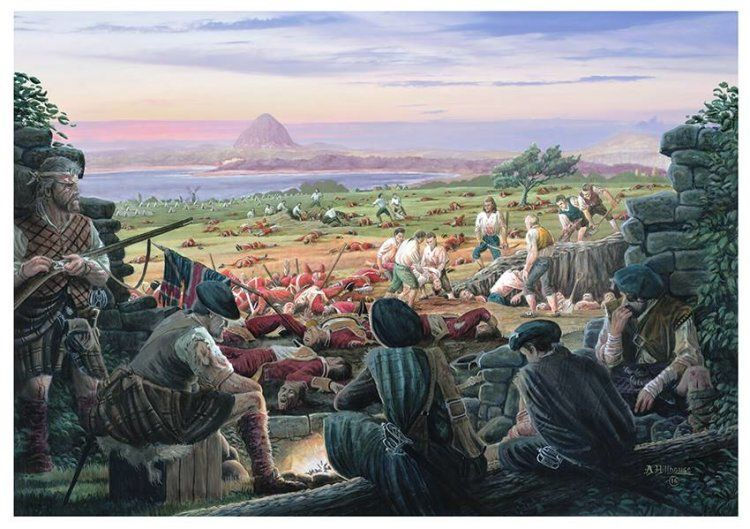

Battle of Prestonpans, 1745 – A small British army was on the wrong end of a Highland Charge when it was attacked by a Jacobite army near Edinburgh. The Redcoats were swept from the battlefield in 30 minutes with about half fallen or captured. For a couple of months at least, Westminster had the spectre of a hostile army on mainland Britain to contend with.

Battle of France, 1940 – An episode most harrowing for British strategic command; when the mass of Allied armies defending northern France, including 13 divisions of the British Army, were absolutely overwhelmed by the German Wehrmacht, wielding its revolutionary blitzkrieg tactics. The Brits suffered 60,000 fallen and captured as well as hundreds of thousands of tons of equipment lost in their dash to evacuate from Dunkirk.