“Modern American war is as easy to script as a B-movie” quipped one US Army officer, referring to the predictability of US victories against its enemies in the late 20th Century. Yet, it wasn’t always smooth sailing for the Yanks.

Presented, the worst US military disaster of every decade spanning the Declaration of Independence til the end of the Cold War – failures little and large that resulted in losses of men and matériel, strategic reversals, and political trauma.

Battle of Long Island, 1776

It was late August 1776 and a year since King George III had proclaimed the ‘Thirteen Colonies’ to be in a state of rebellion. It was also two months since the Continental Congress had enlightened the British as to the true state of affairs; that the ‘colonists’ had broken out of their proverbial egg-shell and the eaglet was flying the nest.

In the opening exchanges, the Patriots forced the British out of Boston and New York. George Washington deduced that the British would strike back to retake the latter, and so they did, sailing back into the mouth of the River Hudson with a rather large fleet of 400 ships conveying 32,000 soldiers. Washington had 19,000 ill-disciplined troops for the city’s defence and a number of forts constructed around the Brooklyn Heights. The upshot of Washington’s strategic dilemma was whether the British would make their main landings at Manhattan or Long Island. He suspected the former but sent 10,000 troops to the latter to guard against any diversionary assault there. This was a fatal miscalculation because it was Long Island where the Brits landed 20,000 troops for their main thrust, and so the Patriot leadership failed to estimate the scale of enemy numbers.

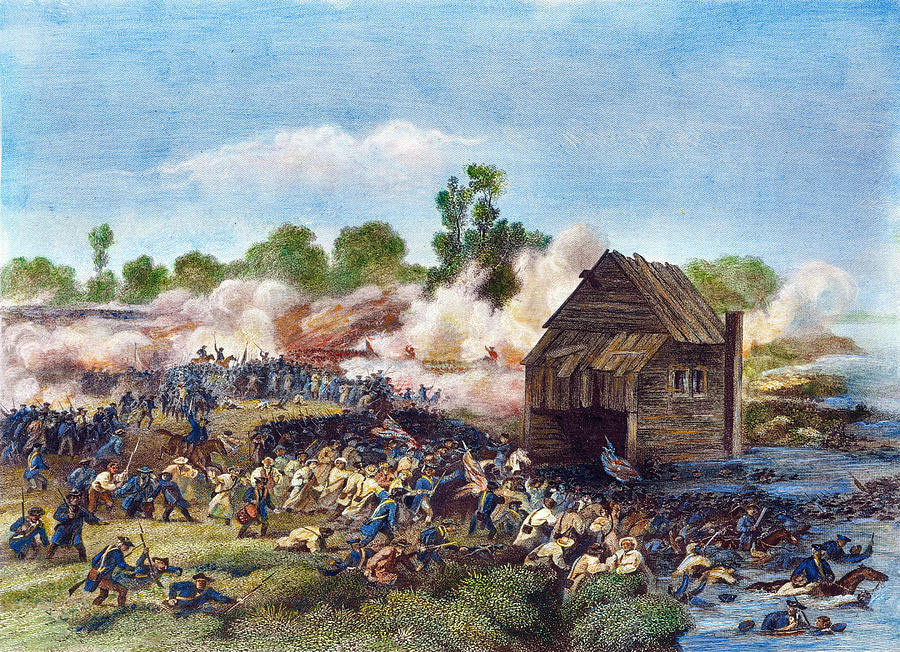

For the coming battle, the Americans planned to face the enemy along a low-lying ridgeline before falling back on the Brooklyn Heights defences. Three passes cut through the ridgeline. The Americans had two well covered yet neglected to guard the third. It was through this pass the British snuck 10,000 men to make a surprise flank attack whilst other battalions held the defenders’ attentions with an ostensible frontal assault. The plan worked a treat. By the morning of the 26th, the Americans believed they were holding well their positions before the true precariousness of their situation became apparent; heavy fire suddenly erupted on their flank. With redcoats and Hessian troops now swarming at them from two sides, the Americans fell into disarray as they struggled to hold it together, panicking as they fought for their lives, swinging desperately with their rifles like clubs. General Sullivan was taken prisoner and the Patriot defenders were decimated – one-in-five were killed or captured in the fighting. They fell back to lick their wounds at Brooklyn Heights and were lucky the British commander failed to follow up an assault on Brooklyn and turn defeat into catastrophe.

Washington realised the defence of the island was now untenable but managed to withdraw his remaining forces back to Manhattan with little further loss. Nevertheless Washington paid a heavy price for his inexperience. Confidence in the Revolution was now shaky. New York was abandoned to the Crown and would remain so until the war’s end.

Siege of Charleston, 1780

The Continental Army had gone from strength to strength and had since triumphed in the battles of Saratoga. Victory was now in sight. The US suffered a shattering setback, however, when its army’s presence in the South was effectively destroyed in May 1780. Britain switched strategic focus to the South, where Crown forces hoped to tap into a hotbed of Loyalist support and capture Charles Town, South Carolina – the region’s economic hub.

The Continentals’ presence in the South was on a weak footing; 6,000 troops defended Charleston, mostly militia forces. General Lincoln was despached to command there – his prize for failing to prise the British from Savannah. The critical weakness of the Patriots’ position was that the city sat on an isthmus that made besieging it an easy enterprise. This the British commenced at the start of April with a polyglot force of 8,000 Loyalists, Germans (and even Irish volunteers) commanded by General Clinton. Despite the siege, Lincoln managed to bring in ships and army units to defend the city for the first couple of weeks. To remedy this porousness, Clinton sent out the Loyalist British Legion to eliminate outlying American positions at Monck’s Corner and Lenud’s Ferry, easily catching them unawares in both battles and suffering very light casualties. With his escape routes gone by early May, Lincoln was clearly in a strategic straitjacket. There was nothing he could do. Once the British started firing heated shot into the city, starting fires, Lincoln was implored to surrender his city. On the 12th of May, he surrendered with over 5,000 men.

With the fall of Charles Town, the Patriots were routed from South Carolina and the entire southern theatre was open to the British.

St. Clair’s Annihilation, 1791

With the British banished, the vast hinterland of North America south of the Great Lakes seemed for the taking but the Native American tribes would show otherwise. After the Revolutionary War, Washington’s administration started grabbing Indian-occupied lands that they could sell to pay off their war debts. Naturally the Native-Americans resisted so, in the summer of 1791, President Washington despatched Major-General St Clair to sweep aside the hostile natives in modern-day Ohio.

St Clair raised a force of regular and militia troops low on morale, numbers and decent equipment. From 2000 men at its peak, this force was whittled down to 900 combat-effectives by the time it encamped on a small hill by the headwaters of the Wabash river on November the 3rd. The Miami, on the other hand, had been joined by allied Indians and had swollen to a force of about 1,400 warriors. On the morning of battle, the Native-Americans were camped and hidden in the surrounding woods and, as the US troops ate breakfast, they attacked, pouncing on the militia initially. The regulars in the main camp were alerted to the unfolding calamity by the sight of panic-stricken militiamen streaming through the camp, their weapons discarded. The regulars seized their own firearms and formed lines to check the onrushing Indian warriors. Within 30 mins the Native-Americans completely surrounded the camp. The order was given to fix bayonets and charge the enemy but each time a unit tried this, the Indians would draw them in before swarming around their flanks and cutting them to pieces. The soldiers were being slaughtered, their injured piling up around the tents joining 200-odd camp followers. After three hours of fighting, St-Clair in desperation gathered up his men to attempt a breakout. Could they save their skins from the ‘Redskins?’ He and just 24 of his most mobile men escaped unharmed. The rest – the slow, wounded, defenceless – were butchered.

About 1/4 of the US Army was wiped out that day. Once news of the catastrophe arrived at the White House, heads rolled. The Native-American Northern Confederation did not take advantage of this overwhelming victory to strengthen their military position, however, as their warriors had familial duties to return to.

Second Battle of Tripoli Harbor, 1803-1804

The Barbary Pirates were the scourge of the Mediterranean and had been for hundreds of years before 1804. These maritime bandits would capture the merchant ships of Christian states and enslave or ransom their crews to provide the rulers of the N. African Barbary states whence they emanated with great wealth and power. It’s estimated that over a million Europeans were enslaved between the 16th and 19th centuries.

The brash, young US Republic would not allow itself to become a victim like its European contemporaries had, and made the commendable decision to stand up to Tripoli with the US Navy’s first major foreign expedition in 1801. Two years later and Commodore Edward Preble assumed command of the U.S. Mediterranean Squadron but, over the next nine months, was impotent in his attempts to blockade Tripoli harbour and lost two warships in the process. In October, the frigate USS Philadelphia, whilst chasing an enemy ship, ran aground two miles offshore. Despite her crew doing everything they could to refloat her, they could not stop the powerful warship from being captured and turned against the Americans as a floating gun battery for the harbour’s defence. What’s more, Philadelphia‘s crew were enslaved. Preble’s only option to mitigate this debacle was to at least deny the warship’s use to the enemy, so he ordered his marines to disable the frigate. In an operation British Admiral Horatio Nelson dubbed: “the most bold and daring act of the age“, they captured a Tripolian ketch which they rechristened the USS Intrepid and, in the dead of night, stormed the Philadelphia, took out her guards before setting the ship ablaze. The blockade continued well into 1804. A series of inconclusive skirmishes did little to hamper the pirates. Preble then ordered a daring mission to convert the USS Intrepid into a fireship laden with explosives to destroy the harbour’s ships, yet the plan backfired. As the ketch approached the harbour mouth, coastal defence guns evidently found their mark and the Intrepid was blown to smithereens along with her crew.

Tripoli eventually submitted in 1805 and the US’s enslaved prisoners were freed, though only after a payment of $60,000 was made. A favourable treaty was signed to end the 1st Barbary War.

Battle of Bladensburg, 1814

Thirty six years after America defeated Britain to gain its independence, the two Anglospheric nations were at it again as the War of 1812 commenced. This was in part due to US ambitions to ‘finish what they started’ and drive the British out of N. America completely, but also a desire to put an end to the Royal Navy’s tyranny over US maritime activity; the Brits had been impressing US sailors and seizing their shipping for some years now and enough was enough.

Out of all the theatres of war, it was the Chesapeake Bay theatre where the British could get at the USA’s ‘soft underbelly.’ Most of the US Army’s regulars were deployed on the Canadian border and Washington DC was left largely for the militia to guard. Major General Ross landed at Benedict, Maryland with about 1,500 infantry plus a Congreve rocket detachment. He then marched his troops towards the nation’s capital and reached Bladensburg on the 24th of August. There the British could cross the Anacostia River then straight into Washington DC. General Winder had 6,000-7,000 troops amassed at Bladensburg to halt Ross’s crack Napoleonic veterans, but they were mostly unreliable militia joined by artillery, dragoons and a naval detachment. Winder had to contend with a number of senior commanders meddling with his troop dispositions around Bladensburg, including Secretary of State Monroe. This resulted in a deplorable defensive setup; among other things, the American artillery was poorly positioned plus militia had been moved off a strong position atop Lowndes Hill. Around noon, the British appeared in Bladensburg and approached the still-standing bridge. Their initial attack across it was repulsed but the redcoats’ subsequent assault through musket and cannon fire secured the west bank. The British then began battering the Americans with Congreve rockets and with that the militiamen lost their stomach for the fight. They melted away in a disorganised rout dubbed the ‘Blandensburg Races.’ The redcoats’ advance now proved irresistable and the rest of the army retreated from the battlefield. The way to Washington DC was now wide open. That night, General Ross and his troops entered the capital city and the US Republic suffered the ignominy of having the White House and US Capitol set ablaze, among other sacred state buildings.

In the sense that an invading force had scattered the government into the wind and then violated the capital city in the most humiliating manner, the Battle of Bladensburg was an utter catastrophe. Yet few troops were lost at Bladensburg and, ultimately, the war would be brought to a satisfactory conclusion.