The story of when the king of Britain adopted a feral child from the forests of Germany into his royal court

When King George I brought a feral boy into the British Royal Court in 1726 he caused a sensation among London’s high society. ‘Peter the Wild Boy’ as he came to be called, neither walked upright or could speak nor write. To many, it seemed he’d surely been raised by wild animals. Yet the truth behind why Peter behaved more animal than man only came out two centuries after his passing when a portrait of the boy was carefully scrutinized.

King’s Feral Forest Boy

So it was that in 1725, King George I of Great Britain returned to his birthplace of Hanover, Germany, and was out hunting in the Hertswold Forest one day.

Amidst a dank, dark grove of beechwood, the King and his hunting party were startled to come across a strange sight.

It was a young adolescent boy scuttling about on all fours like some forest animal. He did not speak but growled and grunted like some guttural, primeval savage.

King George was puzzled by this naked and dishevelled child. He was so at odds with the grace and decorum he’d always known. Had he’d been nurtured by wolves or bears, the King wondered?

He returned from the hunt with this curious child, and a year later the boy, now called Peter, was brought over to London to be transformed from a savage into a gentleman.

Media Sensation

Peter’s arrival quickly became the talk of the town and he became a celebrity; a media sensation who was the subject of newspaper articles, poems and ballads.

This was a time when London was a burgeoning epicentre of European civilization and the Age of Enlightenment was in full flow. Into this intellectual environment, Peter fanned the flames of a debate raging around science and philosophy, nature versus nurture and the delicate line between humans and wild animals.

Questions around whether genetics or environment engendered Peter’s bestial traits, and whether his inability to talk betrayed the absence of a soul or conscience kept the royal court rife with speculation.

Daniel Defoe, of Robinson Crusoe fame, wrote a pamphlet, ‘Mere Nature Delineated’, in which he mused about Peter’s nature. Meanwhile, the linguistic scholar Lord Monboddo, in his ‘Origin and Progress of Language’ presented Peter as an example of his theory of human evolution. Swedish botanist, Carl Linnaeus, even went so far as to create a new category of human in his ‘Systema Naturae’ just for Peter called ‘Juvenis Hanoveranus’.

A wax figure of him was exhibited on Westminster’s Strand, and the renowned satirist Jonathan Swift poked fun at the excitement surrounding his arrival with a pamphlet called ‘The Most Wonderful Wonder that ever appeared to the Wonder of the British Nation’.

Peter’s Palace Life

Once Peter settled in he was treated as something of a pet. Peter charmed the royal household by stealing kisses and cheekily picking the courtiers’ pockets.

Predictably he did struggle to adjust from his life in the undergrowth to one in the plush surroundings of a royal palace, for example making it difficult for palace staff to get him to walk or dress in his green jacket. And the sight of a man once taking off stockings horrified Peter because he thought the man was peeling off his skin.

Dr. Arbuthnot was soon assigned to oversee Peter’s education but he made zero progress in teaching the teenager to speak, read or write. The most he ever achieved was to say his own name and ‘King George’. He did seem to understand much of what was said to him, however.

On balance, Peter seemed more beast than man.

Farm Life and a Pension

In 1727, Peter’s sovereign passed away and he was sent to live out his days on a farm with a handsome annual pension of £35 and his welfare was taken up by a yeoman known to the royal household.

And there, he lived out a long and presumably comfortable life in a laidback rural parish of Northchurch, Hertfordshire where he developed a taste for gin but was known for his general timidity.

He could still get up to mischief, however.

In 1750 Peter went missing. Despite searching far and wide, he could not be tracked down until a nearby jail for vagrants and miscreants caught on fire. In the ensuing evacuation, Peter was identified by his unusual physique and traits.

After that episode, a collar was made for Peter inscribed: ‘Peter, the Wild Man from Hanover. Whoever will bring him to Mr Fenn at Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, shall be paid for their trouble’.

Peter outlived both King George I and II and was well into his 70s when he finally passed away in 1785. He was buried with a gravestone, and flowers are still laid there to this day as a mark of the affection he evoked.

Yet, the scientific mystery around why he failed to cast off his savage ways lay unsolved until as recently as 2011 when a remarkable discovery was made. Painter William Kent included a depiction of Peter in a large painting of King George I’s court that today hangs in Kensington Palace.

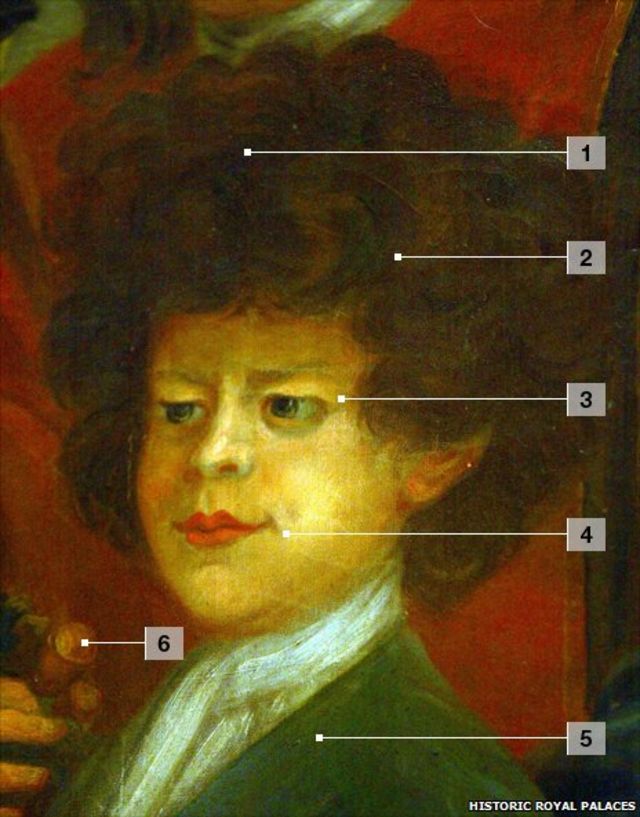

A recent analysis of this portrait by the Institute of Child Health suggests Peter had a rare genetic condition known as Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome, indicated by:

- His short stature

2. Lustrous mop of thick curly hair

3. Hooded eyelids

4. Cupid’s bow mouth, with a pronounced curve to the upper lip

5. He disliked clothes and was wrestled daily into a green suit

6. Pictured holding acorns and oak leaves – symbolic of living wild in the woods – and some fingers on his left hand (not seen) were fused

Pitt-Hopkins is a genetic condition only identified in 1978 and has severe neurological effects. People who have it are characterized by severe learning difficulties, developmental difficulties and the inability to speak. It is thankfully extremely rare; just 500 people have been diagnosed with it across the globe. This discovery would explain why Peter was abandoned in the forest; his parents no doubt struggled to cope with his handicaps.

So, the mystery was solved; ‘Peter the Wild Boy’ was not raised at the teet of a wolf or bear, he was just a boy with a one-in-a-million medical condition.

He was clearly unfortunate in one sense. Nevertheless, Peter was very lucky to encounter His Majesty on that fateful hunt. The King’s interest in Peter’s development did wane with his novelty, but most people with his condition would’ve ended up in a zoo or circus freak show. Peter, however, was treated with care and affection throughout his life.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearly

Leave a comment