It’s a myth that since King William conquered, barely a single foreign attacker has set foot on British shores without some natives in connivance, but here are eight times Britain suffered seaborne raids you might not know about.

Southampton and Portsmouth Sacked, Nearly Destroyed, 1338-9

King Edward III launched a military campaign in 1337 against the French King Philip IV that would escalate into that most epic of wars – the Hundred Years’ War. There was much that initially portended defeat for the French; aggressive raids were radiating out of the English Gascony territory whilst, to the north east, Edward had built a powerful military alliance pregnant with military might. For Edward, however, this all cost a lot of money and England was now in dire financial straits. Philip knew he must turn the screws further by raiding England’s commercial hubs across La Manche – the English Channel. To this end, the King commissioned his north-coast ports to equip ships for raiding and hired Genoese marines to give them teeth.

In March 1338, French raiders sailed into Portsmouth harbour flying English flags. The town had neither a defensive wall nor defenders en garde. Portsmouth was ransacked and most of the town burned to the ground. All who could not flee were slaughtered, raped or taken into slavery. With Portsmouth now out of action, Southampton further inland was next.

In October, 4-12 ships and galleys disgorged perhaps 1000 attackers to deliver the same fate to Southampton. This certainly wasn’t the town’s first rodeo however. They had received advance warning, plus the town possessed a defensive wall, albeit crumbling and 100-200 soldiers and archers were ready to defend the town. As the enemy were sighted sailing up the Solent strait, church bells rang and beacons were lit for reinforcements to come to the town’s aid. The French landed and they swashbuckled their way up the streets before being counterattacked. A desperate fight ensued. One chronicler wrote:

“…they were met by men who soon stopped their game. Some were knocked on the head and died on the spot; some were seeing stars; and some had their brains knocked out. Then they only wanted to escape“.

At this point, the Genoese were called in, elite marines equipped with crossbows to save their French allies from being overwhelmed. With a hail of bolts, the English were driven off. Panic now spread, the townsfolk fled the corsairs or suffered the fate of Portsmouth’s citizens. The blazing city lit up the night sky. With the morning’s high tide, the raiders set sail for home.

Spanish defeat Cornish in Land Battle, 1595

Once upon a time a king wanted a divorce that the Catholic church wouldn’t grant, so he divorced the church instead. Thus began the Reformation – the most turbulent socio-geo-political event in a fair old while and two pertinent conflicts should be noted. Firstly, the Cornish were so opposed to the rejection of Catholicism from England that they launched a serious uprising in 1549 called the Prayer Book Rebellion during which the Catholic Spanish would’ve been welcomed with open arms had they turned up. Secondly, war with Spain kicked off in 1585 in which the Iberians intrepidly launched a grand Armada. England’s plucky sea-dogs famously fought them before ‘God blew and they scattered’ to eventually return home, licking their wounds.

But the Spanish menace was not driven away yet. At Mount’s Bay, where Great Britain’s ‘tiptoe’ thrusts into the deep blue Atlantic, four galleys filled with arquebusiers sailed over the southern horizon in late summer of 1595 and made landfall, being guided by an English Catholic named Richard Burley. 200 soldiers came ashore and marched inland to burn down the village of Paul and its church whilst Mousehole was fired upon by the galleys’ cannons, setting fire to many houses.

These marauding Spanish were not done yet, the soldiers re-embarked on the ships and the next day set sail to cause more havoc up the coastline. But Sir Thomas Godolphin was waiting for them. He heard of the invading force from fleeing villagers and had summoned the local militia. When the Spaniards re-landed at Penzance, Godolphin had a reception party of 500 Cornish men-at-arms on the beach. Sighting this force arrayed against them, the Spanish knew their venture was in peril. They advanced on the enemy and their brethren on the ships fired their cannons at the Cornishmen. But these local defenders had no stomach, not against their Catholic allies, at least. As they came under fire they scattered from the battlefield leaving Godolphin and just 12 of his servants to stand up to the invaders. The way was now clear and Penzance was in the palm of the foreign devils’ hands. They torched the town and the homes of 400 residents were said to have been burned down. With the raid a sterling success, the Spanish held mass on a hill above the town and the priest vowed to build a friary there in two years time once England was conquered. The force then set sail for home after releasing their prisoners.

The Spanish raid had actually been predicted by Cornish people long before. There had been a saying in Cornish:

Ewra teyre a war mearne Merlyn

Ara lesky Pawle, Pensanz ha Newlyn

They shall land on the Rock of Merlin

Who shall burn Paul, Penzance and Newlyn

The Rock of Merlin is at Mousehole, where the Spanish soldiers came ashore.

Barbaric Barbars Kidnap Sixty Cornish-folk, 1625

It wasn’t just the Spanish that Englishmen scanned the southern horizon for. From out of North African ports Barbary pirates were becoming an ever greater menace. These pirates became the scourge of maritime Christendom between the 15th-18th centuries to such an extent that hundreds of thousands of Christians were enslaved from captured ships and slave raids ashore in the Mediterranean. These brazen, barbaric pirates, joined by a smattering of European sailors who had turned to the dark side, acquired the seafaring know-how to range as far north as the Netherlands, Ireland and even Iceland.

England also suffered. Destined one day to ‘rule the seven seas’, the island nation was as incapable of guarding against the pirate menace as any. By the early 1600s it was stated in the Calendar of State Papers in May 1625 that: “The Turks are upon our coasts. They take ships only to take the men to make slaves of them.” And Sir John Eliot, Vice Admiral of Devon, declared that the seas around England “seem’d theirs.” Dozens of Barbary ships lurked around Penzance, causing the kingdom great anxiety that turned to downright panic in August 1625 when the pirates landed at Mount Bay and captured 60 men, women and children, dragging them away to a life of slavery.

Royal Navy Humiliated by Attack on Chatham Docks, 1667

The English and Dutch fought a series of wars between 1652 and 1784 to establish naval and maritime supremacy. In the First Anglo-Dutch War, the Dutch started well, but the English managed to clear the seas of their North-Sea rivals. This ended the war in 1654. It seemed Dutch courage had dried up but they were not out of the fight yet.

In 1665, the 2nd War commenced after the Frisians rebuilt their fleet and the two belligerents traded blow for blow in the early exchanges. English economic strength was at a low ebb, however; knocked first by a plague then the Great Fire of London in 1666. Subsequently, much of Charles II‘s greatest warships were laid up due to ‘budget cutbacks’. It was now that the Dutch saw their chance to kick the English while they were down.

On the 6th of June a fog bank in the Black Deep – the seaway leading into the Thames estuary – cleared to reveal a fleet of 90 Dutch warships. To the south, the mouth of the River Medway gaped open with Chatham Docks located at the river’s oesophagus where most of the King Charles’ major warships were laid up. Although it would actually take the Dutch five days to reach Chatham, morale was low across the Navy’s command, and confusion reigned which explains the poor English reaction to the enemy in their midst. The enemy made an amphibious assault on Sheppey Isle to capture and demolish the fort there before venturing on upstream. Chatham was guarded by a castle and had a chain across the river, plus blockships were hastily sunk. Yet, as the orange-flagged enemy advanced, a crack force of engineers landed and broke the chain with hammers. The English defence was ineffectual because most of the ships were undermanned or not manned at all. The attackers suppressed defensive fire whilst expending eight fire-ships to sink 13 ships in and around the docks. But the English themselves sank 30 of their own ships to deny them to the Dutch as Andrew Marvell satirised: “Of all our navy none should now survive, but that the ships themselves were taught to dive”

The Dutch returned home in a blaze of glory, suffering light casualties and leaving London in full-blown panic in their wake. As Samuel Pepys conceded: “Thus in all things, in wisdom, courage, force, knowledge of our own streams, and success, the Dutch have the best of us, and do end the war with victory on their side”.

Futile Land Invasion by French, 1690

It was two years into the Nine Years’ War between France and a ‘Grand Coalition’ of England, the Holy Roman Empire and the Dutch Republic – an ally this time; hardly surprising given that a Dutchman, King William of Orange, was two years into his reign as King of England, instigated by an ‘invasion’ of his own by some metrics.

Anyway, the war was going well for the French and the English Channel was theirs after victory in the Battle of Beachy Head. Instead of following up their advantage however, Admiral De Tourville’s fleet headed west and anchored off Torbay. All of Devon’s forces had massed to defend the town so De Tourville thought it would do much to advance France’s war aims if he despatched a landing force seven miles east to Teignmouth instead. Sailing in close and bombarding the unfortified town, several hundred French troops were landed. For 12 hours they plundered and set fire to dozens of houses, destroyed the harbour’s ships and “killed very many cattle and pigs which they left dead in the streets”. Because the war was religious in nature, they despoiled two of Teignmouth’s churches also. The fleet sailed off into the sunset.

Their devastation of Teignmouth caused panic across the land. The diarist John Evelyn wrote, “The whole nation now exceedingly alarmed by the French fleet braving our coast even to the very Thames mouth”. Yet, Tourville’s attack had achieved nothing. He could’ve taken advantage of his freedom of movement around English waters to sail into the Irish Sea to cut off King William from returning from Ireland. William defeated the French-backed King James in the Battle of the Boyne just the next day to underline the wasted opportunity.

Traitor Saves Whitehaven from Audacious US Raid, 1778

In 1778, the USA was three years into its fight to break free from the shackles of imperial rule when John Paul Jones entered the history books. He became the first commander of renown in the embryonic US Navy because of his plucky exploits throughout the war.

Yet Jones was an officer of mixed ability. On one hand he was ambitious and flourished under the maxim ‘fortune favours the brave’, capturing sixteen merchant ships and inflicting significant damage in the raid on Canso during a six-week voyage in 1776, for example. On the other hand, his leadership skills were not fantastic, judging from the fact crews mutinied not once but twice under his command in which he killed a man on both occasions. Regardless, he was good at making friends in high places. In 1777, Jones was despatched to France in order to bring the fight to British waters.

It was as Captain Jones cruised the Irish Sea he had the idea to attack Whitehaven in Cumbria. He had started out his career there and therefore knew the town well (being born in Scotland). Whitehaven was crammed with hundreds of ships. If a landing party could get into harbour and start a fire, with the many coal transports present, the whole harbour would go up in smoke, rattling the British and spreading great cheer back across the Atlantic. It could’ve gone so well for Jones …his crew were less than keen on the venture however.

The plan was for one party to start a fire in the northern half of the harbour while Jones led a raid on the fort to spike the guns. Jones’ party successfully disabled the fort but as they emerged, the Captain was concerned with the lack of an orange tint coming from the direction of the harbour to indicate ships ablaze. The other group’s incendiaries had extinguished and this was just the excuse to head for the nearest pub for some liquid refreshment, finally emerging in a substantially sozzled state. Dismayed, Jones finally gathered up his men and went to set fire to a coal-ship. But a spanner was then thrown into the works. Jones’ men were so sullen one of them went down the streets, waking up the residents to warn them what was happening. A fire finally took hold on the coal-ship but the alerted townsfolk rushed to the harbourside and rapidly put out the fire. Frustrated, Jones stormed off with his men to make their escape out to sea.

Large French Force Deterred by Welsh Locals, 1797

It was on a wild Celtic coastline at the dusk of the 18th Century where foreign forces last landed on a British beach. The French revolutionary 1st Republic hatched a plan to wreak havoc in the British Isles and keep the British too busy to interfere on the continent. That plan involved a major invasion of Ireland to help the Irish Brotherhood fight the British off their island whilst further diversionary invasions were planned in the North and South West of England. By January of 1797, however, the Irish and northern English invasions had been scuppered, largely down to the inclement weather. Despite this, the attack on Bristol was given the go-ahead.

More disagreeable weather prevented a delve into the Bristol Channel, and so, it was in February that four warships of the invasion fleet arrived off Fishguard and were greeted by cannon fire, warning the locals that the enemy was now in their midst. On the 22nd, 1400 soldiers landed at Llanwnda. Whilst 600 men of the force, called La Légion noire were first-rate Grenadiers the rest were unreliable penal troops. As such, these miscreants began deserting, looting amongst the homesteads and getting drunk on stocks of Portuguese wine that had recently washed ashore.

British Army units were not on-hand to fight off the French in this isolated corner of Britain, yet the locals reacted energetically to the enemy’s landing; what militia there was were called up, plus locals armed and organised themselves and a woman named ‘Jemima Fawr’ even managed to single-handedly corral 12 French stragglers into captivity. The British, however, were severely out-gunned and the prospect of facing French regular troops was a daunting one. Nevertheless, 600 militia, dragging along three cannon approached the French and almost blundered into an ambush. By the night of the 23rd, French officers approached the British commander for a conditional surrender, given that half the French force had either deserted or were not obeying orders. The British rejected the offer and informed them they had until the morning to surrender unconditionally. The British resolved to march down to Goodwick Sands to take surrender of the enemy or fight and die, come what may. The French were not fully aware of the weak forces arrayed ahead of them. They also sighted many redcoats troops on the clifftop behind – these ‘redcoats’ were actually local women dressed in traditional Welsh garb of red shawls and black bonnets who had come to watch proceedings. Cowed, the French commander surrendered and by 4pm the French troops laid down their muskets.

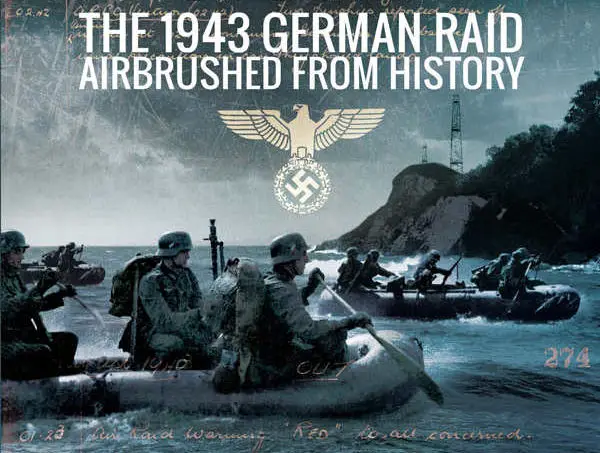

Germans Steal Radar Equipment from Isle of Wight, 1943?

If one consulted the University of Oxford’s history professors, they would repeat the proud boast of Britain’s that, despite the grave threat of invasion by the mighty German war machine, no enemy managed a landing on British shores in World War II. Yet, it is claimed that on the 15-16th of August 1943, 10 German soldiers were transported from the occupied Channel Islands by submarine and landed on the Isle of Wight in inflatable dinghies to steal a valuable piece of radar equipment.

These claims were made by a highly respected historian and archivist, Dr Dietrich Andernacht, and an anonymous former naval officer who both took part in the raid. They also stated three prisoners were taken after a British patrol engaged them in a firefight, injuring one German for the deaths of two Tommies. Also, when the radar technology was later examined, it had a self-destruction device which exploded when dismantled by technicians.

The story is substantiated by reports of two British servicemen stationed on the island who had no business ending the war in German POW camps. The story of the raid is told in: Churchill’s Last Wartime Secret.

Leave a comment